AFI 1-CITZEN KANE

In addition to writing about the films of my youth I also wrote in FACEBOOK my experiences with all sorts of films. Those I saw for the first time on TV and those I saw first on Home Video. I also began writing about the American Film institute (AFI) 100 greatest Americans. So in my blog posts, I am going to mix them up all together. Here is the number one on the AFI list.

CITIZEN KANE

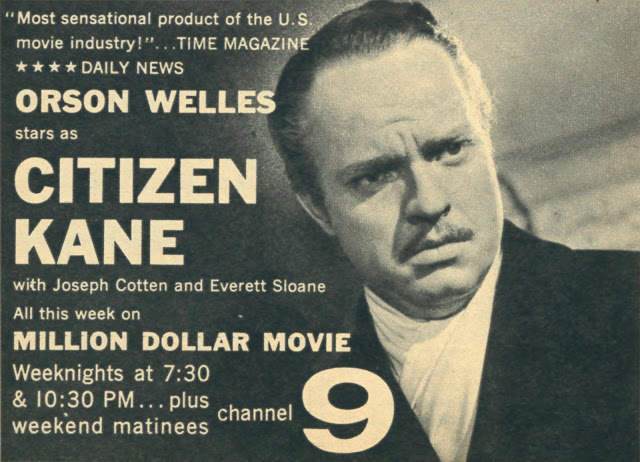

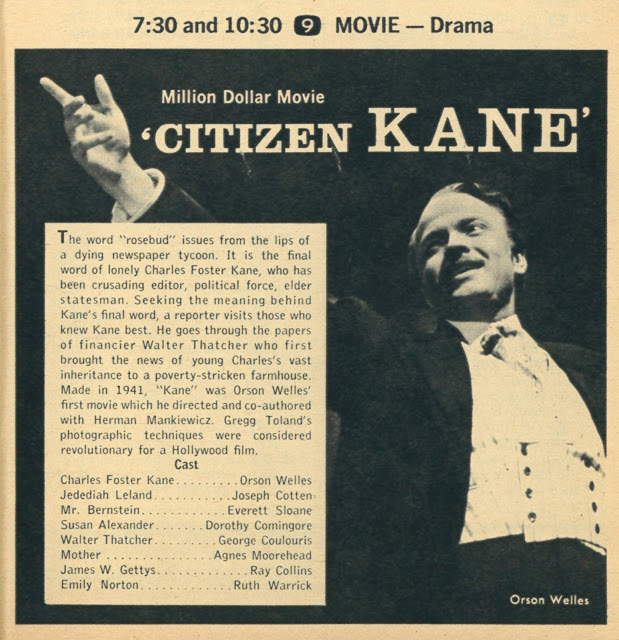

The first time I saw CITIZEN KANE was in the mid-1950s on the Million Dollar Movie. Channel 9, a local New York TV Station, would show the same film on the Million Dollar Movie twice a day for a week. I was of course a pre-teen at the time and remember clearly the station promoting the film mentioning that it was considered the greatest film of all time by critics. I believe this was from the time of the film’s original release in which it was called just that by many critics.

The story behind this TV showing is rather interesting. After Howard Hughes ran RKO into the ground C&C Cola purchased the TV rights to most of the RKO Library. Working with 16MM prints which is what Local TV used in those days, the company removed the RKO logo from the front of these films and replaced it with C&C Presents. They then gave use—for free—the entire library to TV stations around the country. The only stipulation was that they were to run without charge C&C commercials during the film showings. And that’s how I got to see Citizen Kane for the first time. It is also interesting to note that the film had been unavailable to the general public since it was taken out of release in (I think 1943) and had gone into eclipse. It was these 1950s TV showings that got the film seen again by the public and that’s when the present day evaluation of the film really began and the legend that came with it went into the popular lexicon.

At the time I saw the film, remember I was a pre-teen, I couldn’t figure the dam thing out and turned it off midway to look at Leave it to Beaver or the Donna Reed Show. Those I could understand although my family was nothing like the families in those saccharine but extremely enjoyable TV shows. Maybe that is why they were so enjoyable.

The next time I saw the film was maybe 10 years later. By this time I was a teenager with a keen interest in film and had read some pieces on the film and so had a better understanding of what I was about to watch. Janus Films had leased the Theatrical rights and along with the APA were presenting some of their films at the Belasco Theater in New York and CITIZEN KANE was among these films. I actually had to go down to the theater and purchase a reserved seat a week or so before. On the day of the showing the theater was packed and what they were presenting was a Nitrate print. In fact a reel was missing and they substituted a 16mm nitrate reel. Take my word if you haven’t seen a film in nitrate, you haven’t seen it. This time I understood what the film was doing and sat through to the end. I can say that I enjoyed it—sort of—but still thought to myself “what is all the fuss about.” What I do remember clearly is leaving the theater and walking beside a couple—the woman in her twenties and the man in his forties—armes rapped around each other. The woman was chattering away and I remember her saying, “It was bad, but it was wonderfully bad.” Then as now I didn’t have any idea what she was talking about. Talk about New York pretentious.

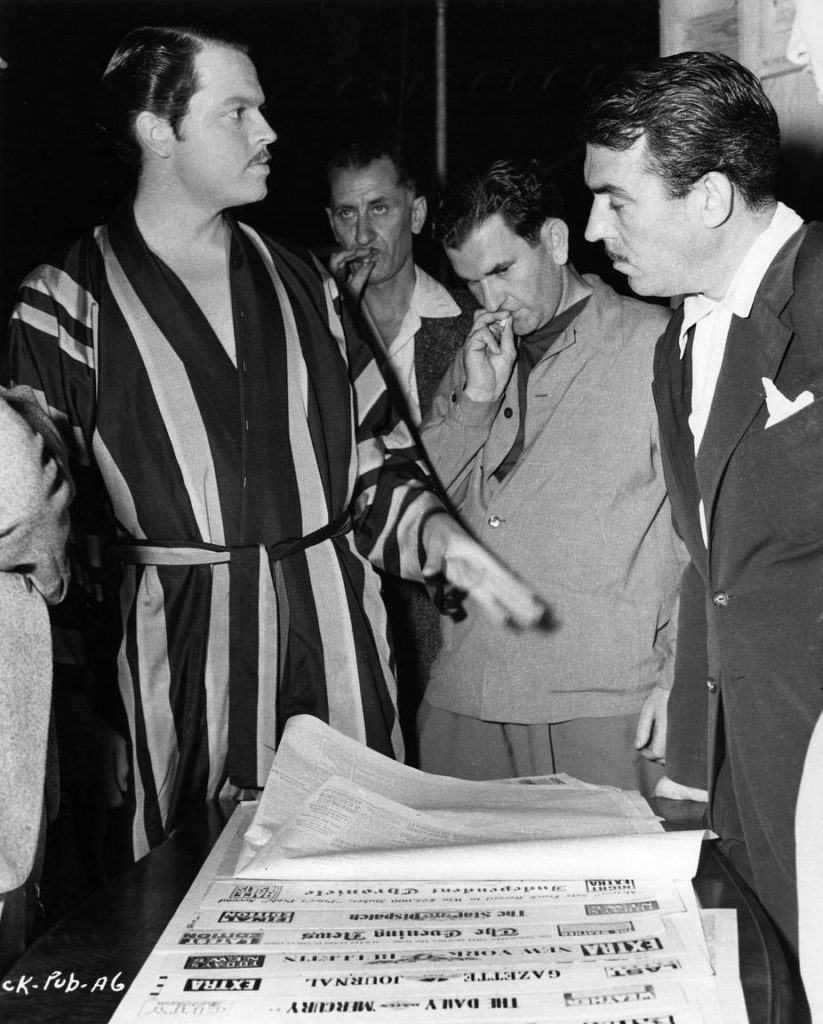

In my sophomore year at college I had a chance to see the film once again at a College Film Society showing. By this time I knew a great deal more about movies as I had read every film book in the college library and having access to bound volumes of the New York Times had had gone through the Times entertainment sections day by day from 1915 thru 1947 when the college library had switched over to microfilm. So I already knew that the film had first opened at New York’s RKO Palace as a Roadshow and was called ORSEN WELLES CITIZEN KANE. I knew the whole back story about Hearst and all hoopla that occurred during the film’s release and the fact that the film had underperformed at the box office and at an $850,000 cost had not recovered its money. This was the time of the Pauline Kael-Peter Bogdanovich public squabble over who was really the “author” of the film, Welles or Herman Mankiewiciz. Also, and the shooing script was published as the Citizen Kane Book with an intro by Pauline Kael which was really her two-part article on the film originally published in The Yorker.

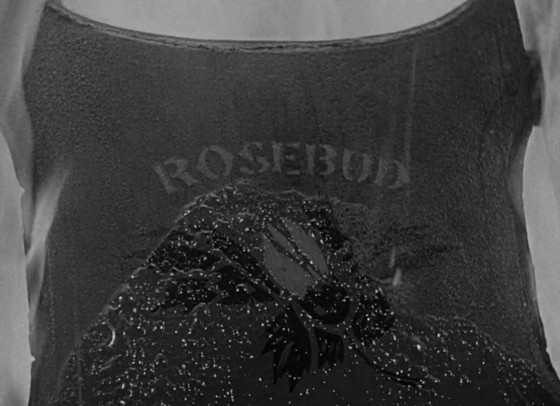

This time though I finally could understood what I was watching. Welles (as with Egoyan and Tarantino after him) was using the film to break with the linier form used by movies since the beginning of the medium (INTOLERANCE being a rare exception) and using the Rosebud business as a sort of detective element to tell a story on film in a completely new way. Example; the Newsreel business gets the chronology out of the way so the rest of the film could jump about as it used interviews giving insights into who the lead character really was. (Which turned out to be all men to all people as each of the characters interviewed had a different take on the man.) And finally the jigsaw puzzle overhead tracking shot of Kane’s collection (some of the items we recognize and some not) with the Rosebud sled thrown into the fire, the flames revealing the name as the old varnish burned off and finally the NO TRESSPASSING sign telling us that it is impossible to sum a man’s life; a visual re-statement of what the reporter says earlier. But as this occurs after the statement, that brilliant overhead tracking shot with the sled into the fire, it has far more impact and as it is pure cinema and a clear demonstration of the power of images over words. And of course, don’t forget the Bernard Herrmann music.

Then of course there are the brilliant cinematic touches Welles uses many of which he brought in from the theater. With genius cinematographer Greg Toland helping him, Welles was able to do things with the camera that had never been done before and all in one film. A good example: presenting a photograph of the Chronical Staff and then Welles walking into the picture as it transform into live action. There is so much more and anyone who has seen the film probably remembers all of them, as Welles displays Welles with no shame in bringing attention to them in a dazzling and brilliant display of cinematic virtuosity. There is not a moment in the film that we are allowed to forget that we are watching a film.

People have dismissed Kane by intimating that the Rosebud business is a gimmick—I disagree as it was merely a story telling tool that got the ball rolling and kept it rolling—and the film really has nothing profound to say. This is something that I also disagree with. The film is an illuminating study of the experience of a life; its initial optimism and later disappointments. Also, you can only get glimpses of a life. In short a life is something inexplicable. The same man to you may not be the same man to me or even himself/herself. In this respect the film reminds me of a Whitman poem from Leaves OF Grass in which the writer discusses the inability of words to convey human experience as human experience with regards to words is inexplicable.

In any case I could write pages on the film but if you are really interested in the subject I suggest you get your hands on The Making OF Citizen Kane by Robert L. Carringer. It is a brilliant piece of academic detective work in which he traces the making of the film as to who did what and how it was all done. Reading it will answer most questions you might have about the film. I have read the book twice and, much like the film whose making it chronicles, I never grow tired of reading it.